Become JEWiSH

SPEAK LIKE A REAL NATIVE

AUTHENTIC JEWISH LIVING

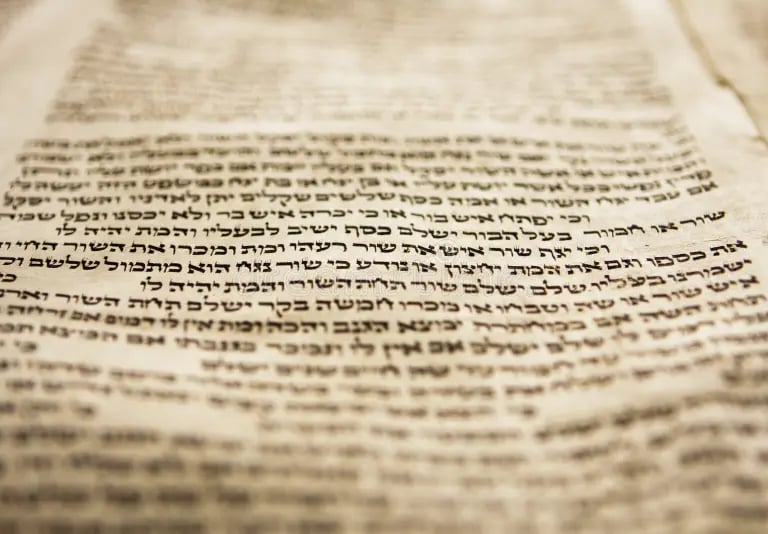

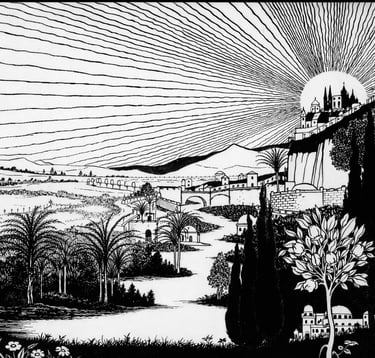

From its ancient roots in the Iron Age kingdoms of Israel and Judah to the modern revival of the Hebrew language in the 19th and 20th centuries, the Hebrew-speaking world has played a pivotal role in global history. Its cultural tapestry reflects influences from ancient Near Eastern civilizations, Hellenistic and Roman rule, centuries of diaspora life, and the profound legacy of biblical tradition. With its extraordinary historical landmarks—from ancient fortresses and sacred cities to vibrant modern neighborhoods—Israel offers a timeless journey through a rich and enduring cultural legacy.

After the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, the country underwent a dramatic transformation. Waves of immigration brought together Jewish communities from Europe, the Middle East, North Africa, and beyond, creating a multilingual, multicultural society unified by the revival of Ivrit. Over the decades, Israel embraced political, social, and technological development, becoming known for its scientific innovation, advanced education system, and fast-growing economy. Its thriving arts scene, expanding tourism industry, and global leadership in technology and research showcase a country that honors its complex past while shaping a dynamic future.

We have created a selection of words and expressions that you won’t find in any textbook or course, to help you become more native-like by understanding Hebrew terms that carry deeper cultural meaning and by expanding your knowledge of Israel, its people, and its history.

EXPAND YOUR KNOWLEDGE

If you are serious about learning Hebrew, we recommend that you download the Complete Hebrew Master Course.

You will receive all the information available on the website in a convenient portable digital format as well as additional contents: over 15.000 Vocabulary Words and Useful Phrases, in-depth explanations and exercises for all Grammar Rules, exclusive articles with Cultural Insights that you won't find in any other textbook so you can amaze your Jewish friends or colleagues thanks to your knowledge of their culture and history.

With a one-time purchase you will also get more than 10 hours of Podcasts to Practice your Hebrew listening skills as well as Dialogues with Exercises to achieve your own Master Certificate.

Start speaking Hebrew today!

AFIKOMAN

The afikoman (אפיקומן, dessert or after-meal portion) is a central element of the Jewish Pesach (פסח, Passover) Seder, symbolizing both tradition and memory in Jewish ritual practice. Derived from a Greek term meaning “that which comes after,” the afikoman refers to a piece of matzah (מצה, unleavened bread) set aside early in the meal and consumed at the end, serving as the final taste of the Seder night. Its presence links ancient Temple customs, post-Temple remembrance, and modern domestic ritual in a single act of symbolic continuity.

During the Seder, the head of the household breaks the middle matzah and hides one half as the afikoman, an action known as tzafun (צפון, hidden). This piece is later searched for, usually by children, in a playful custom that keeps them engaged throughout the evening. The recovered matzah becomes the concluding food of the Seder, eaten after the festive meal to recall the korban pesach (קרבן פסח, Passover sacrifice) once offered in the Temple in Jerusalem. By eating the afikoman in silence, participants symbolically partake in the ancient offering, connecting domestic ritual to the historical act of collective redemption.

The practice also carries educational and psychological dimensions. The search for the afikoman embodies the principle of chinuch (חינוך, education), reinforcing the pedagogical nature of the Seder night, when families transmit Jewish identity and memory across generations. Parents may promise a sachar (שכר, reward) to the child who finds the afikoman, blending joy with moral instruction. The hidden matzah serves as a tangible representation of hope and anticipation, illustrating the transition from slavery to freedom that defines Passover’s narrative arc.

Halakhically, the afikoman must be eaten before chatzot (חצות, midnight), following the order established by rabbinic authorities. According to the Mishnah (משנה, early rabbinic code), no food should follow it so that its taste remains in the mouth, a rule that preserves the meal’s spiritual closure. This detail reflects the centrality of memory in Jewish observance: the act of eating the afikoman ensures that the liberation story remains the final and enduring sensation of the night.

Beyond ritual precision, the afikoman symbolizes the endurance of Jewish continuity. Hidden, sought, and rediscovered, it mirrors the historical resilience of the Jewish people—concealed at times yet never lost. Through this simple piece of matzah, generations reaffirm the core ideals of faith, freedom, and remembrance that define the Seder experience.

AMUD

The amud (עמוד, podium or stand) is a central fixture in the layout of a synagogue, serving as the place from which the shaliach tzibur (שליח ציבור, prayer leader) conducts communal worship. Positioned traditionally before the aron kodesh (ארון קודש, holy ark), the amud stands as both a physical and spiritual focal point within the sanctuary. The word itself means “pillar” or “column,” symbolizing steadfastness and support, much like its role in upholding the structure of public prayer.

Historically, the amud developed alongside the architectural and liturgical evolution of the synagogue. In early Jewish worship, prayer leaders stood among the congregation, but as services became more structured, a designated location was needed for visibility and audibility. The amud thus emerged as an essential component of synagogue design, enabling the chazan (חזן, cantor) to lead readings from the siddur (סידור, prayer book) and to coordinate responses between the congregation and the divine service. Its placement varies slightly among communities, reflecting diverse customs between Ashkenazim (אשכנזים, Jews of Central and Eastern European descent) and Sephardim (ספרדים, Jews of Iberian and Middle Eastern descent).

In many traditions, the amud is reserved for those reciting Kaddish (קדיש, memorial prayer) for deceased relatives, symbolizing the mourner’s role in sustaining faith amidst loss. Standing at the amud signifies assuming communal responsibility and spiritual leadership, even temporarily. For this reason, it is often considered an honor to approach the amud, reflecting both humility and devotion. The person leading prayers from this spot represents the collective voice of the congregation before God.

The amud’s design may range from simple wooden stands to elaborately carved pieces adorned with inscriptions. In Sephardic synagogues, it sometimes functions in tandem with the teivah (תיבה, reading platform), while in Ashkenazic practice, the amud typically faces the ark, aligning prayer toward Jerusalem. Regardless of form, it embodies the principle of kavod hatzibur (כבוד הציבור, respect for the community), ensuring that worship is both dignified and participatory.

Beyond its physical structure, the amud carries metaphorical weight in Jewish thought. Just as a pillar supports a building, so does the act of leading prayers from the amud sustain the spiritual framework of Jewish continuity. Each individual who stands there reinforces the communal bond linking generations of worshippers. Through the amud, the ancient ideal of collective prayer—voices united in reverence and supplication—finds enduring expression in every synagogue across the world.

ARBA MINIM

The arba minim (ארבעה מינים, four species) are four specific plants used during the Jewish festival of Sukkot (סוכות, Feast of Tabernacles), symbolizing unity, gratitude, and the harmony of diverse human qualities. The four species—lulav (לולב, palm branch), etrog (אתרוג, citron), hadassim (הדסים, myrtle branches), and aravot (ערבות, willow branches)—are waved together in ritual processions and prayers throughout the week of the festival. The practice derives from the Torah commandment in Vayikra (ויקרא, Leviticus) 23:40, where the faithful are instructed to “rejoice before the Lord” with these species, transforming natural elements into instruments of worship.

Each component of the arba minim carries symbolic meaning. The etrog, fragrant and edible, represents individuals who combine knowledge and good deeds. The lulav, which has taste but no scent, symbolizes those who possess learning but lack action. The hadassim, known for their pleasant fragrance but lacking taste, signify people of good deeds without extensive study. The aravot, having neither taste nor smell, represent those who contribute neither wisdom nor virtue. When bound together, they embody the essential unity of the Jewish people, teaching that collective harmony arises from mutual inclusion rather than uniformity.

The ritual of waving the arba minim, called na’anuim (נענועים, shaking motions), involves moving the bundle in six directions—east, south, west, north, up, and down—to acknowledge divine presence in all realms of existence. This gesture transforms a simple agricultural act into a profound spiritual statement: that human life, like nature, is sustained through recognition of divine omnipresence. The ceremony is performed inside the sukkah (סוכה, temporary hut), reinforcing the festival’s themes of impermanence, dependence on nature, and faith in divine protection.

In halacha (הלכה, Jewish law), the selection of the arba minim is highly detailed, emphasizing beauty and perfection. The etrog must be unblemished, the lulav straight, the hadassim and aravot fresh and green. These physical criteria symbolize moral integrity and the aspiration toward spiritual wholeness. According to midrashic interpretations, the four species also correspond to different parts of the human body: the spine (lulav), the heart (etrog), the eyes (hadassim), and the lips (aravot)—reminding worshippers that every faculty should be directed toward divine service.

Over centuries, the arba minim have come to express both agricultural gratitude and spiritual unity. Farmers once brought these symbols of harvest to the Temple in Jerusalem; today, Jewish communities around the world continue the same gestures, maintaining continuity with their ancestral faith. The act of holding and waving the arba minim encapsulates the balance between individuality and collectivity, earthly existence and divine presence, grounding the Sukkot celebration in both joy and reverence.

ASHKENAZIM

The Ashkenazim (אשכנזים, Jews of Central and Eastern European descent) form one of the major cultural and historical branches of the Jewish people. The term “Ashkenaz” originally referred to the region associated with medieval Germany, and over time came to designate Jewish communities that developed across Central and Eastern Europe, including Poland, Lithuania, Russia, and Hungary. Distinct from the Sephardim (ספרדים, Jews of Iberian and Middle Eastern descent), the Ashkenazim developed unique religious customs, liturgical melodies, and linguistic traditions that continue to shape global Jewish identity today.

The emergence of Ashkenazic culture began in the early Middle Ages, when Jewish communities settled along the Rhine River. There, they blended biblical, Talmudic, and local influences into a distinctive form of Jewish life. The halachic (הלכתי, legal) tradition of the Ashkenazim was shaped by scholars such as Rashi (רש"י, Rabbi Shlomo Yitzhaki) and later codified by Rabbi Moshe Isserles in his glosses to the Shulchan Aruch. These texts remain foundational in defining the ritual practices, prayer customs, and legal interpretations that distinguish Ashkenazic Judaism from other traditions.

The everyday language of the Ashkenazim was Yiddish (יידיש, Jewish-German language), a fusion of medieval German dialects with elements from Hebrew, Aramaic, and Slavic languages. More than a means of communication, Yiddish carried the emotional and cultural world of Eastern European Jewry, preserving folklore, humor, and ethical wisdom through generations. Ashkenazic literature, from Hasidic tales to modern writers like Sholem Aleichem and Isaac Bashevis Singer, reflects the resilience and creativity of communities that flourished despite persistent adversity.

Religiously, the Ashkenazim contributed to diverse spiritual movements, including Hasidism (חסידות, pietistic movement) and its rationalist counterpart, the Mitnagdim (מתנגדים, opponents). Hasidism, founded by Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov, emphasized joy, prayer, and spiritual immediacy, while the Mitnagdim, led by the Vilna Gaon, focused on rigorous study of the Talmud (תלמוד, rabbinic text). The dialogue between these movements profoundly shaped Jewish spirituality, blending mysticism with intellectual depth.

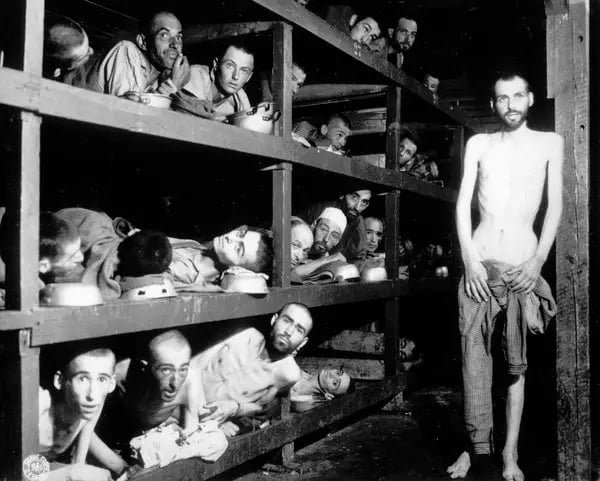

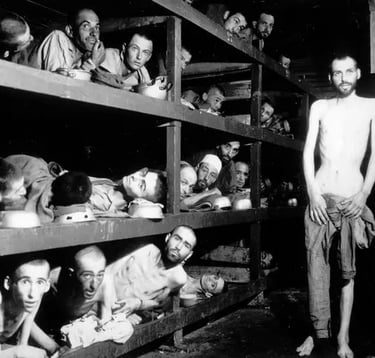

The tragedies of the Holocaust nearly annihilated European Ashkenazic civilization, yet its legacy endures across the globe. Today, descendants of Ashkenazim form the majority of Jews in Israel, North America, and Europe, maintaining traditions such as distinctive prayer chants, liturgical pronunciations, and holiday foods like gefilte fish (געפילטע פיש, stuffed fish dish). Their influence extends to philosophy, music, politics, and science, where figures of Ashkenazic origin have played pivotal roles in shaping modern Jewish and world culture.

The history of the Ashkenazim is ultimately one of adaptation and perseverance—of communities rebuilding their spiritual and cultural worlds wherever they settled. Their contributions to Jewish thought, law, and identity continue to affirm the enduring vitality of the Ashkenazic heritage within the broader mosaic of the Jewish people.

BALFOUR DECLARATION

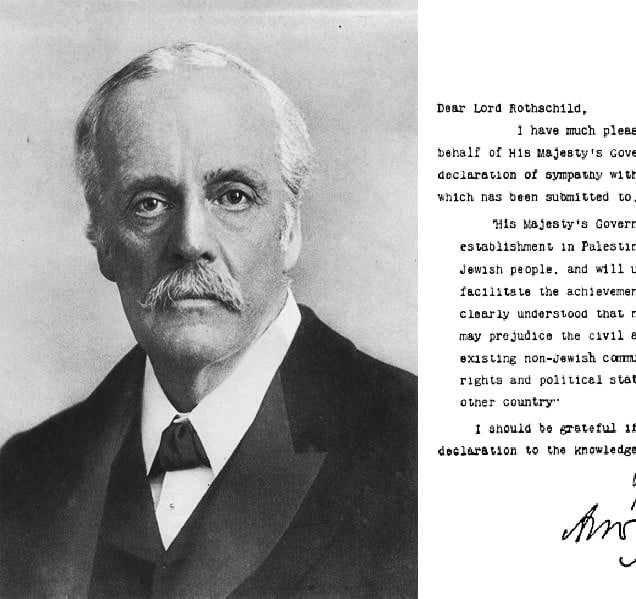

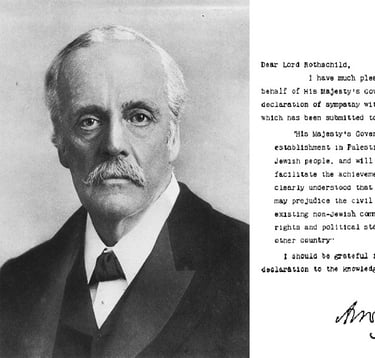

The Balfour Declaration (הצהרת בלפור, Balfour Declaration) was a landmark statement issued by the British government on November 2, 1917, expressing support for the establishment of a “national home for the Jewish people” in Eretz Yisrael (ארץ ישראל, Land of Israel). It was conveyed in a letter from Foreign Secretary Arthur James Balfour to Lord Rothschild, a leading figure in the British Jewish community, and became one of the foundational documents in the history of modern Zionism (ציונות, Jewish national movement). Though short in wording, the declaration had immense political, moral, and diplomatic significance, influencing the trajectory of Jewish and Middle Eastern history in the twentieth century.

The text of the declaration stated that “His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people,” while adding that nothing should prejudice the rights of existing non-Jewish communities. This balancing clause reflected the complex geopolitical realities of World War I, during which Britain sought both Jewish and Arab support. The issuance of the declaration followed decades of Zionist advocacy led by figures such as Theodor Herzl (תיאודור הרצל, founder of modern Zionism), whose vision of a Jewish homeland gained international legitimacy through this document.

From a diplomatic standpoint, the Balfour Declaration represented the first official endorsement by a major world power of Jewish aspirations for self-determination. It was later incorporated into the Mandate for Palestine (המנדט על פלשתינה, British administrative framework), approved by the League of Nations in 1922, which legally recognized Britain’s responsibility to facilitate Jewish immigration and settlement. This created the institutional foundation for the eventual establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, making the declaration a turning point in Jewish modern history.

However, the document also became a source of deep controversy. Arab populations in Palestine and neighboring regions viewed it as a betrayal of earlier wartime promises made to support Arab independence. The dual commitments within the British Mandate—to both Jewish and Arab communities—proved irreconcilable, leading to escalating tensions, uprisings, and the enduring conflict over the land. Historians continue to debate whether the Balfour Declaration was an act of moral restitution to a dispersed people or a strategic maneuver within imperial politics.

In Jewish collective memory, the Balfour Declaration is remembered as a diplomatic milestone that transformed the dream of return into a recognized political objective. Its issuance symbolized the convergence of faith, perseverance, and global diplomacy. More than a century later, its legacy remains embedded in the modern history of Israel and continues to shape discussions on sovereignty, identity, and the quest for peace in the Middle East.

BAMIDBAR

The Bamidbar (במדבר, In the Wilderness) is the Hebrew title of the fourth book of the Torah (תורה, Law or Teaching), known in English as the Book of Numbers. The term bamidbar literally means “in the desert,” reflecting both the geographical and spiritual setting of Israel’s journey from Mount Sinai toward the Promised Land. This period of wandering, lasting forty years, represents a formative stage in the development of Israelite identity, marked by trial, organization, rebellion, and divine guidance. The book is foundational for understanding the transition from a newly liberated people to a nation bound by covenant and law.

Bamidbar opens with a census, the source of the English title “Numbers.” The mifkad (מפקד, counting or census) symbolizes order and preparation for nationhood. Each tribe is counted and positioned within the machaneh (מחנה, camp), surrounding the Mishkan (משכן, Tabernacle), which serves as the spiritual and physical center of the community. This organization emphasizes unity through structure, showing that holiness requires discipline and collective responsibility. The arrangement of the tribes around the Mishkan mirrors cosmic harmony, with divine presence at the center radiating outward to all aspects of national life.

The book also recounts a series of journeys and trials, illustrating the tension between faith and doubt. Episodes such as the complaints over food, the rebellion of Korach (קרח, Korah), and the incident of the meraglim (מרגלים, spies) demonstrate the challenges of maintaining trust in divine leadership. These narratives are not mere historical accounts but moral lessons about human frailty and perseverance. Each failure becomes an opportunity for renewal, teaching that spiritual growth often arises through hardship.

Bamidbar also introduces laws related to purity, inheritance, and leadership, shaping Israel’s social and moral framework. The story of Bilam (בלעם, Balaam) and his attempted curse against Israel highlights divine protection and the futility of human opposition to God’s will. Through such accounts, the text underscores that Israel’s survival depends not on military strength but on fidelity to the covenant. The final chapters recount victories east of the Jordan and the preparation for entering Eretz Yisrael (ארץ ישראל, Land of Israel), signaling both the end of wandering and the beginning of national realization.

In Jewish tradition, Bamidbar is read in synagogues during late spring and early summer, a period that symbolically aligns with movement and transition. Its themes—faith in uncertainty, leadership, communal organization, and divine presence amid struggle—remain timeless. Bamidbar teaches that the wilderness is not a place of abandonment but a crucible where identity, resilience, and holiness are forged.

BAR KOCHBA

The Bar Kochba (בר כוכבא, Son of the Star) revolt was one of the most significant Jewish uprisings against the Roman Empire, taking place between 132 and 135 CE. Led by Shimon Bar Kochba (שמעון בר כוכבא, Simon Son of the Star), the rebellion aimed to reestablish Jewish sovereignty in Eretz Yisrael (ארץ ישראל, Land of Israel) after decades of Roman domination. The name Bar Kochba derives from a messianic interpretation of the prophecy in Sefer Bamidbar (ספר במדבר, Book of Numbers) 24:17, “A star shall come forth out of Jacob,” reflecting hopes that he was the long-awaited deliverer of Israel.

The revolt emerged in response to the harsh policies of the Roman Emperor Hadrian (הדריאנוס, Hadrian), who banned circumcision and planned to rebuild Jerusalem as a pagan city named Aelia Capitolina with a temple to Jupiter on the site of the destroyed Beit HaMikdash (בית המקדש, Temple). Outrage over these decrees united Jewish fighters, religious leaders, and farmers in a determined resistance movement. Bar Kochba, described by contemporary sources as both charismatic and disciplined, organized a well-trained army and established an independent Jewish administration with minted coins bearing the inscription “Year One of the Redemption of Israel.”

For nearly three years, the rebels succeeded in creating a de facto Jewish state, restoring national pride and religious practice. According to Rabbi Akiva (רבי עקיבא, Rabbi Akiva), one of the greatest sages of the era, Bar Kochba was initially believed to be the Mashiach (משיח, Messiah), a conviction that strengthened morale and unity. However, the revolt eventually provoked a massive Roman counteroffensive under General Julius Severus. The ensuing battles were brutal, with devastating losses on both sides. The final stand occurred at Beitar (ביתר, Beitar), southwest of Jerusalem, where Bar Kochba and tens of thousands of his followers were killed in 135 CE.

After the defeat, the Romans imposed severe reprisals: Judea was renamed Syria Palaestina, Jewish access to Jerusalem was forbidden, and Torah study was banned. These decrees deepened the galut (גלות, exile), transforming Jewish life from a national to a diasporic existence. Yet the memory of Bar Kochba endured as a symbol of courage and the yearning for redemption. In rabbinic literature, he is portrayed with ambivalence—both as a heroic leader and a cautionary figure whose failure arose from overconfidence.

Modern Jewish history has reinterpreted Bar Kochba as a symbol of resistance and national revival. In the early Zionist movement, he was celebrated as an emblem of Jewish bravery and independence. Youth organizations, sports clubs, and literary works invoked his name to inspire physical and spiritual renewal. Through centuries of exile, the story of Bar Kochba continued to embody the enduring spirit of self-determination rooted in Jewish history.

BAR MITZVAH

The bar mitzvah (בר מצוה, son of the commandment) is a central rite of passage in Jewish tradition marking the moment when a boy assumes full religious responsibility. At the age of thirteen, he becomes obligated to observe the mitzvot (מצוות, commandments) of the Torah (תורה, Law), transforming from a minor under parental duty to an individual accountable before God. The bar mitzvah ceremony reflects not only personal maturity but also the transmission of communal identity, symbolizing the continuity of faith, learning, and moral obligation within Jewish life.

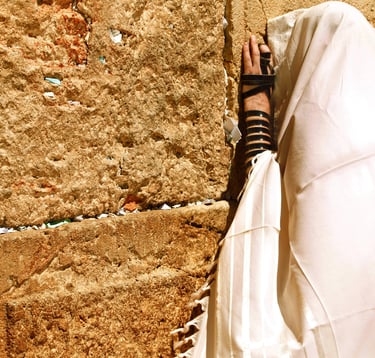

The origins of the bar mitzvah trace back to rabbinic sources in the Talmud (תלמוד, rabbinic code), which designate thirteen as the age of religious majority for males. While no specific ritual is prescribed in biblical law, medieval communities developed ceremonial expressions to honor the transition. The boy is called to the bimah (בימה, synagogue platform) to read from the Sefer Torah (ספר תורה, Torah scroll), publicly demonstrating his new status as a participant in communal worship. This act, known as aliyah laTorah (עלייה לתורה, ascent to the Torah), remains the focal point of the celebration across Jewish denominations.

In traditional communities, the bar mitzvah may also include the boy leading parts of the tefillah (תפילה, prayer service), reciting blessings, or delivering a short speech called derashah (דרשה, sermon), reflecting on the weekly Torah portion. The family often hosts a festive seudah (סעודה, meal) afterward, emphasizing joy and gratitude. Customs vary across the Jewish world: among Ashkenazim (אשכנזים, Jews of Central and Eastern Europe), the event often centers on synagogue participation, while Sephardim (ספרדים, Jews of Iberian and Middle Eastern descent) may place greater focus on communal feasting and blessings.

Symbolically, the bar mitzvah represents the passage from dependence to responsibility. The young man now counts toward the minyan (מניין, quorum for prayer), can wear tefillin (תפילין, phylacteries), and is eligible to serve as a witness or reader in religious ceremonies. This transition emphasizes autonomy within the framework of divine law, teaching that freedom and responsibility coexist within covenantal life. The bar mitzvah also reflects a family’s success in transmitting chinuch (חינוך, education), affirming the intergenerational bond that sustains Jewish continuity.

In modern times, the bar mitzvah has acquired additional cultural and social dimensions. In many communities, it serves as a moment of public affirmation of identity, blending tradition with contemporary expression. Large gatherings, music, and celebrations may accompany the religious core, yet the essence remains spiritual: the acknowledgment of a young person’s entry into the covenant of Israel. Across centuries and continents, the bar mitzvah has endured as a unifying ceremony that integrates learning, faith, and communal belonging into a single transformative milestone.

BAT MITZVAH

The bat mitzvah (בת מצוה, daughter of the commandment) marks the coming of age for Jewish girls, symbolizing their assumption of moral and religious responsibility within the community. Traditionally celebrated when a girl turns twelve, one year earlier than a boy’s bar mitzvah (בר מצוה, son of the commandment), the event recognizes her new status as obligated to observe the mitzvot (מצוות, commandments) and participate fully in Jewish spiritual life. The phrase bat mitzvah does not appear in the Talmud (תלמוד, rabbinic code), yet its concept is rooted in halakhic principles that define maturity through accountability before God.

Historically, the public celebration of a bat mitzvah is a modern development. For centuries, Jewish women assumed religious obligations privately without formal ceremony. The first recorded public bat mitzvah occurred in 1922 when Judith Kaplan (יהודית קפלן, Judith Kaplan), daughter of Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan, founder of the Reconstructionist (רקונסטרוקציוניסטי, Reconstructionist) movement, read from the Torah (תורה, Law) in New York. Her act marked a pivotal step in expanding women’s participation in Jewish ritual life, inspiring similar observances across denominations. Today, the bat mitzvah is a common ceremony in Reform, Conservative, and increasingly in Modern Orthodox communities.

The ceremony often mirrors the structure of the bar mitzvah, though customs vary. The girl may be called to the bimah (בימה, platform) to recite blessings, read from the Sefer Torah (ספר תורה, Torah scroll), or lead sections of tefillah (תפילה, prayer). In more traditional settings where women do not read publicly, she might deliver a derashah (דרשה, sermon) or host a study session focusing on a Torah topic. The family typically holds a seudah (סעודה, festive meal), emphasizing the joy and spiritual significance of the occasion.

Beyond ritual participation, the bat mitzvah reflects evolving conceptions of gender and equality in Jewish life. It affirms the principle that women, like men, bear covenantal responsibility for moral and spiritual action. The ceremony often includes themes of tzedakah (צדקה, charitable giving) and community service, linking personal celebration to social ethics. For many families, the preparation period—studying Hebrew, prayers, and Jewish history—strengthens identity and commitment to tradition.

In Israel and the diaspora alike, the bat mitzvah has become both a religious and cultural milestone. While its forms differ—ranging from intimate synagogue gatherings to large community events—the essence remains the same: a declaration of belonging and maturity. Through the bat mitzvah, Jewish girls affirm their place in the continuum of faith and learning, carrying forward the spiritual legacy of their ancestors into modern life.

BEIT KNESSET

The beit knesset (בית כנסת, house of assembly) is the Hebrew term for the synagogue, the central institution of Jewish communal and religious life. Functioning as a space for tefillah (תפילה, prayer), Torah (תורה, teaching), and social gathering, the beit knesset has served as both a spiritual sanctuary and a communal hub throughout Jewish history. Its name emphasizes the collective aspect of worship—the coming together of the kahal (קהל, congregation)—highlighting the idea that holiness is not only individual but shared among those who gather in faith and purpose.

The origins of the beit knesset date back to the galut Bavel (גלות בבל, Babylonian exile) in the sixth century BCE, when Jews, deprived of access to the Beit HaMikdash (בית המקדש, Temple), created local places for study and prayer. These early houses of assembly became vital centers of religious continuity. After the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, the beit knesset emerged as the permanent locus of Jewish worship, replacing sacrifices with prayer and study as the primary expressions of devotion. This transformation marked a decisive shift from Temple-centered to text-centered spirituality, ensuring the survival of Jewish practice across exile and dispersion.

Architecturally, the beit knesset reflects both function and faith. Traditional synagogues are oriented toward Yerushalayim (ירושלים, Jerusalem), symbolizing unity with the ancient holy city. The interior typically includes the aron kodesh (ארון קודש, holy ark), which houses the Sefer Torah (ספר תורה, Torah scroll); the bimah (בימה, reading platform); and the ner tamid (נר תמיד, eternal light), representing the continuous presence of God. The amud (עמוד, lectern) stands before the ark, where the shaliach tzibur (שליח ציבור, prayer leader) leads the congregation in worship. Each element serves not merely a ritual function but a symbolic one, weaving together memory, reverence, and communal participation.

The beit knesset has always been more than a place of prayer. It serves as a center for education, charity, and communal decision-making. Within its walls, children learn in the beit midrash (בית מדרש, house of study), elders deliberate over community matters, and families mark life-cycle events such as bar mitzvah (בר מצוה, coming of age) or chuppah (חופה, wedding ceremony). This integration of sacred and social life reflects the Jewish vision of holiness as extending beyond ritual into everyday action.

Across time and geography—from medieval Spain to modern Israel—the beit knesset has remained a constant symbol of resilience and unity. Even in times of persecution, Jews risked their lives to maintain these sanctuaries, preserving identity through prayer and learning. Today, the beit knesset continues to serve as the living heart of Jewish communities worldwide, linking past devotion to future generations through the unbroken rhythm of collective worship.

BEIT MIDRASH

The beit midrash (בית מדרש, house of study) is the traditional center of Jewish learning, dedicated to the study of Torah (תורה, Law), Talmud (תלמוד, rabbinic code), and other sacred texts. The term literally means “house of interpretation,” emphasizing not only the transmission of knowledge but also the process of inquiry, debate, and renewal that defines Jewish intellectual life. In every generation, the beit midrash has served as both a physical space and a spiritual ideal—a place where study itself becomes an act of worship and community building.

The origins of the beit midrash can be traced to the early rabbinic period, following the destruction of the Beit HaMikdash (בית המקדש, Temple) in 70 CE. As Temple sacrifices ceased, study and prayer replaced ritual offerings as the core of Jewish devotion. The rabbis taught that “Talmud Torah keneged kulam” (תלמוד תורה כנגד כולם, the study of Torah is equal to all other commandments), placing learning at the heart of religious life. In the beit midrash, scholars, students, and laypeople gather to engage in chevruta (חברותא, study partnership), a method of dialogue and argumentation designed to sharpen understanding through mutual challenge and reflection.

The beit midrash differs from a formal school in its open, dynamic character. It functions as a communal study hall rather than a structured classroom. Rows of wooden tables, shelves filled with commentaries, and the hum of discussion create an atmosphere of intellectual energy and devotion. Here, learning is pursued not for personal gain but for lishmah (לשמה, its own sake), expressing the conviction that studying sacred texts connects the human mind with divine wisdom.

Historically, every Jewish community sought to maintain a beit midrash, whether attached to a beit knesset (בית כנסת, synagogue) or operating independently. In medieval Europe, the great yeshivot (ישיבות, academies) of Mainz, Worms, and Vilna evolved from this model, producing generations of scholars who codified halacha (הלכה, Jewish law) and guided Jewish life across the diaspora. In modern times, the beit midrash continues to flourish in institutions ranging from Israeli yeshivot to university departments of Jewish studies, blending traditional scholarship with contemporary methods of textual analysis.

The beit midrash remains a symbol of Jewish resilience and intellectual continuity. It embodies the belief that faith thrives through questioning and that truth emerges from dialogue. Even today, when a student opens a book and begins to debate an ancient passage, the chain of learning that stretches back to Sinai is renewed. The beit midrash thus stands as a living testament to the power of study to sustain identity, community, and spiritual depth across the centuries.

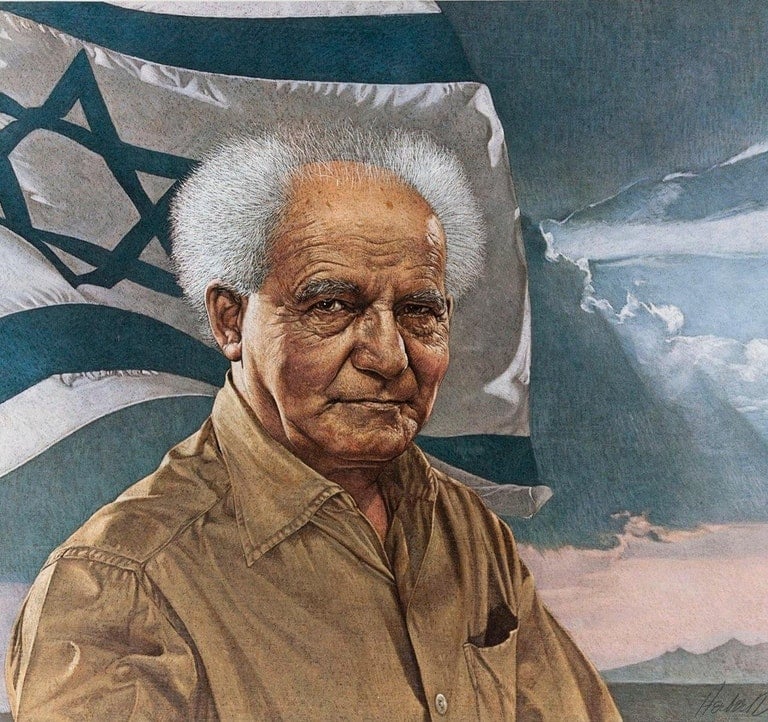

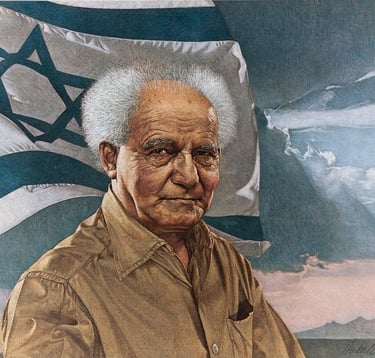

BEN-GURION

David Ben-Gurion (דוד בן גוריון, David Ben-Gurion) was the founding father and first Prime Minister of the Medinat Yisrael (מדינת ישראל, State of Israel), a leader whose vision and determination transformed the dream of Jewish nationhood into political reality. Born in 1886 in Płońsk, then part of the Russian Empire, he was originally named David Grün. Deeply influenced by early Zionist (ציוני, Zionist) ideals, he emigrated to Ottoman Palestine in 1906, joining the growing movement of Jewish pioneers working the land and reviving the Hebrew language. His name change to Ben-Gurion—derived from a historical figure mentioned in the Talmud (תלמוד, rabbinic text)—symbolized his embrace of national renewal and historical continuity.

In pre-state Palestine, Ben-Gurion emerged as a central political organizer and thinker. As a member of the Poalei Tzion (פועלי ציון, Workers of Zion) party, he advocated for a labor-based model of settlement and governance. He helped found the Histadrut (הסתדרות, General Federation of Labor) in 1920, an institution that became the economic and social backbone of the Jewish community under British rule. His political leadership culminated in his role as head of the Jewish Agency (הסוכנות היהודית, Jewish Agency), where he directed immigration efforts, defense preparation, and negotiations with British authorities during the Mandate (מנדט, Mandate) period.

On May 14, 1948, Ben-Gurion proclaimed Israel’s independence in Tel Aviv, reading the Megillat HaAtzmaut (מגילת העצמאות, Declaration of Independence) and establishing the first Jewish state in nearly two thousand years. As Prime Minister and Minister of Defense, he guided the new nation through the Milchemet HaAtzmaut (מלחמת העצמאות, War of Independence), securing survival against multiple invading armies. His policies emphasized state-building, immigration absorption—particularly of Jewish refugees from Arab lands and Holocaust survivors—and the creation of a unified national army, the Tzva HaHagana LeYisrael (צבא ההגנה לישראל, Israel Defense Forces).

Ben-Gurion’s leadership combined pragmatism with idealism. He believed the state must balance spiritual heritage with modern governance. His promotion of aliyah (עלייה, immigration to Israel) and chalutziut (חלוציות, pioneering spirit) shaped the country’s demographic and ideological foundation. Yet his tenure was not without controversy: debates over religion and state, the handling of Arab populations, and relations with the diaspora all sparked enduring divisions. Nevertheless, his vision of a secure, self-reliant, and ethically guided Israel remained at the heart of national discourse.

After retiring from politics, Ben-Gurion settled in Sde Boker (שדה בוקר, Field of the Cowboy), a kibbutz in the Negev Desert, where he devoted himself to writing, study, and promoting desert development. His life embodied the synthesis of intellect, action, and faith in renewal that defines modern Jewish identity. Revered as both a statesman and a symbol, Ben-Gurion’s legacy continues to influence Israel’s political culture, defense strategy, and moral consciousness.

BERACHA

The beracha (ברכה, blessing) is a fundamental concept in Jewish religious life, expressing gratitude, sanctification, and acknowledgment of divine presence in daily experience. Rooted in the Hebrew verb levarech (לברך, to bless), the beracha serves as both a linguistic and spiritual act, transforming ordinary actions into moments of holiness. By reciting blessings over food, natural phenomena, commandments, and life events, Jews affirm the belief that every aspect of existence derives meaning through connection with HaShem (השם, the Name of God).

A typical beracha follows a standardized structure beginning with the words Baruch Atah Adonai Eloheinu Melech HaOlam (ברוך אתה ה׳ אלוהינו מלך העולם, Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the Universe), followed by a phrase specific to the occasion. This formula reflects both humility and intimacy—acknowledging God’s sovereignty while addressing the divine directly. Through repetition of this formula, daily life becomes an ongoing dialogue with the Creator, infusing routine actions with sacred intention or kavanah (כוונה, spiritual focus).

There are three primary categories of berachot. The first includes blessings over physical pleasures, such as food and drink, divided into types like hamotzi (המוציא, bread), mezonot (מזונות, grain-based foods), hagafen (הגפן, wine), and ha’etz (העץ, fruit of the tree). The second type encompasses blessings of mitzvot, recited before performing commandments such as netilat yadayim (נטילת ידיים, ritual handwashing) or hadlakat nerot (הדלקת נרות, lighting candles). The third category, known as berachot hoda’ah (ברכות הודאה, blessings of gratitude), responds to natural wonders, survival from danger, or moments of joy—recognizing divine providence in human life.

The concept of beracha extends beyond verbal recitation. It reflects a worldview in which gratitude and mindfulness are central virtues. The rabbis of the Talmud (תלמוד, rabbinic code) taught that one should strive to say at least one hundred blessings each day, emphasizing constant awareness of divine generosity. By acknowledging God’s role in even the smallest aspects of life, the individual cultivates humility and moral clarity. Each beracha serves as a reminder that creation is ongoing and that human consciousness participates in sustaining it.

In contemporary practice, the beracha continues to bridge ancient tradition and modern experience. Whether whispered over a morning coffee, sung in communal worship, or spoken during moments of crisis, the blessing maintains its timeless role as a tool of connection. It transforms the physical into the spiritual and the fleeting into the eternal. Through the simple act of uttering a beracha, Jewish life becomes a continuous sanctification of existence, uniting word, intention, and gratitude in the presence of the divine.

BRIT MILAH

The brit milah (ברית מילה, covenant of circumcision) is one of the oldest and most significant rituals in Judaism, symbolizing the eternal bond between the Am Yisrael (עם ישראל, people of Israel) and HaShem (השם, the Name of God). Performed on the eighth day after a male child’s birth, the brit milah fulfills the divine commandment given to Avraham Avinu (אברהם אבינו, Abraham our forefather) in Sefer Bereshit (ספר בראשית, Book of Genesis) 17:10–12, establishing a physical and spiritual covenant that has been maintained continuously for thousands of years.

The ceremony involves the removal of the foreskin by a trained practitioner known as the mohel (מוהל, circumciser), followed by the recitation of blessings and prayers. During the rite, the child is given his Hebrew name, formally entering the covenantal community of Israel. The father recites the blessing “להכניסו בבריתו של אברהם אבינו” (to bring him into the covenant of our father Abraham), reaffirming the continuity of the Jewish lineage and the transmission of faith from generation to generation. The brit milah thus serves not only as a biological act but as a profound spiritual initiation connecting the individual to the collective destiny of the Jewish people.

Historically, the practice of brit milah has been maintained even under persecution, reflecting its centrality to Jewish identity. During periods of oppression—from the decrees of the Seleucid Empire under Antiochus IV to anti-Jewish policies in the Roman and later European eras—Jews risked their lives to uphold this mitzvah. The ritual became a symbol of resilience and fidelity to divine command, a visible marker of covenantal loyalty that could not be erased by assimilation or coercion.

In halachic (הלכתי, legal) terms, brit milah is categorized as a positive, time-bound commandment. It is performed ideally during daylight hours, even on Shabbat (שבת, Sabbath) or Yom Tov (יום טוב, festival), emphasizing its spiritual priority. If health concerns delay the procedure, it is postponed until the child’s recovery, underscoring Judaism’s commitment to pikuach nefesh (פיקוח נפש, preservation of life). The mohel must be both technically skilled and spiritually aware, ensuring that the act is performed in accordance with Jewish law and reverence.

In modern Jewish life, brit milah remains a unifying ritual across diverse communities—Ashkenazim (אשכנזים, Central and Eastern European Jews), Sephardim (ספרדים, Jews of Iberian and Middle Eastern descent), and Mizrachim (מזרחים, Jews of Eastern lands). Even among secular Jews, it endures as a powerful symbol of belonging and continuity. Though occasionally debated in contemporary discourse, its deeper meaning persists: brit milah expresses the inseparable link between physical identity and spiritual covenant, a living affirmation of the ancient promise that defines the Jewish people.

BIRKAT HAMAZON

Bentsching (בענטשן, from Yiddish; referring to Birkat HaMazon ברכת המזון, Grace After Meals) is the traditional Jewish practice of reciting a series of blessings after eating a meal that includes bread. Rooted in the biblical commandment “Ve’achalta ve’savata u’veirachta” (ואכלת ושבעת וברכת, “You shall eat, be satisfied, and bless”), bentsching transforms an ordinary act of nourishment into a moment of spiritual awareness. Rather than focusing on anticipation before eating, it emphasizes gratitude after one’s needs have been fulfilled, reinforcing mindfulness, humility, and recognition of sustenance as a gift rather than a given.

The structure of Birkat HaMazon consists of four primary blessings. The first thanks God for providing food; the second expresses gratitude for Eretz Yisrael (ארץ ישראל, the Land of Israel); the third centers on Yerushalayim (ירושלים, Jerusalem) and collective spiritual longing; and the fourth acknowledges divine goodness and mercy. Together, these blessings weave personal satisfaction with national memory and communal responsibility, linking the individual dining table to Jewish history and identity across generations.

Bentsching is traditionally recited aloud when people eat together, especially during Shabbat (שבת) and festivals, turning the table into a shared ritual space. In many households, melodies and familiar rhythms accompany the words, making the practice both participatory and intimate. Special additions are included on holy days, weddings, or celebrations, allowing the text to respond to the emotional and spiritual context of the moment while maintaining its fixed core.

Historically, bentsching has adapted linguistically and culturally. While the original text is in Hebrew, explanatory phrases and customs developed in Yiddish-speaking communities, giving rise to the colloquial verb “to bentch.” Printed bentchers (booklets for Birkat HaMazon) often reflect local artistic styles and communal traditions, preserving continuity while accommodating regional expression.

CHALLAH

The challah (חלה, braided bread) is one of the most recognizable and symbolic foods in Jewish tradition, primarily associated with Shabbat (שבת, Sabbath) and Yom Tov (יום טוב, festival) meals. While the term originally referred to the portion of dough set aside as an offering to the kohanim (כהנים, priests) during the Temple era, it later came to denote the rich, braided loaves baked for sacred occasions. The act of separating challah fulfills a biblical commandment found in Sefer Bamidbar (ספר במדבר, Book of Numbers) 15:20–21: “Of the first of your dough, you shall give to the Lord an offering.” This simple household act transforms baking into a ritual of sanctification and remembrance.

In ancient times, the hafrashat challah (הפרשת חלה, separation of the dough) served as a tangible expression of gratitude and devotion. Women, traditionally responsible for this mitzvah, would set aside a small piece of dough and burn it or discard it in memory of the priestly gift once offered in the Beit HaMikdash (בית המקדש, Temple). Even after the Temple’s destruction, the practice continued as a symbolic link to holiness and continuity, preserving the idea that physical nourishment is intertwined with spiritual purpose. The blessing recited—Baruch Atah Adonai... le’hafrish challah min ha’isa (Blessed are You, Lord... who has commanded us to separate challah from the dough)—sanctifies the ordinary act of baking.

Over centuries, the challah evolved in form and meaning. In medieval Ashkenazic communities, the custom of braiding loaves emerged, symbolizing unity and intertwined blessings. Two loaves are placed on the Shabbat table, recalling the lechem mishneh (לחם משנה, double portion of manna) that fell for the Israelites in the wilderness before Shabbat. The glossy, golden crust—often brushed with egg wash—reflects abundance and joy. Sephardic communities, by contrast, often bake round or spiral challot, particularly during Rosh Hashanah (ראש השנה, New Year), to represent the cyclical nature of time and divine mercy.

Beyond its ritual function, challah carries social and emotional significance. It is a centerpiece of family gatherings, embodying warmth, hospitality, and the sanctity of domestic life. In many homes, baking challah has become a communal activity that unites generations, blending tradition with creativity. In contemporary Jewish culture, the mitzvah of separating challah has also gained renewed popularity among women’s study groups and spiritual circles as a meditative practice linking faith and everyday life.

Thus, challah stands as more than bread—it is a living symbol of covenant and gratitude. Through its preparation, separation, and blessing, the simple act of baking transforms into a declaration of continuity, celebrating both the nourishment of the body and the sanctification of the household.

CHAZAN

The chazan (חזן, cantor) is the individual who leads the congregation in tefillah (תפילה, prayer) within the beit knesset (בית כנסת, synagogue). Serving as both spiritual leader and musical guide, the chazan ensures that communal worship is conducted with reverence, rhythm, and precision. In traditional Judaism, the role combines technical mastery of Hebrew liturgy with deep personal devotion, as the chazan acts as the shaliach tzibur (שליח ציבור, representative of the community), articulating collective supplication before HaShem (השם, the Name of God).

Historically, the office of chazan emerged during the early rabbinic period when public prayer replaced sacrificial worship after the destruction of the Beit HaMikdash (בית המקדש, Temple). Because many congregants could not recite the prayers by heart, one individual was chosen to chant them aloud on behalf of all. Over time, this function developed into a respected religious profession. By the Middle Ages, communities across Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East appointed trained cantors whose roles combined musical artistry, halachic knowledge, and pastoral sensitivity.

The chazan’s duties extend beyond leading services. In many traditions, he supervises the pronunciation and melody of the nusach (נוסח, prayer mode), ensuring continuity of liturgical tradition. Each prayer—morning, afternoon, and evening—has its own musical motifs reflecting the mood of the text and the character of the festival cycle. During the Yamim Nora’im (ימים נוראים, High Holy Days), when themes of repentance and awe dominate, the chazan’s voice conveys emotional depth and solemnity, guiding the congregation toward teshuva (תשובה, repentance).

Becoming a chazan requires rigorous preparation. Classical training includes mastery of ta’amei hamikra (טעמי המקרא, cantillation marks), traditional melodies, and precise enunciation of Hebrew liturgy. In modern times, professional cantorial schools—particularly within Ashkenazic communities—offer comprehensive programs combining music theory, voice training, and Jewish studies. Notable institutions such as the Hebrew Union College–Jewish Institute of Religion and Israel’s Academy of Music have produced generations of cantors who blend ancient motifs with contemporary artistry.

Beyond musical skill, the chazan embodies spiritual leadership. He is often called upon to officiate at life-cycle events such as weddings, funerals, and bar or bat mitzvah ceremonies, offering comfort and inspiration through song. In smaller congregations, he may also serve as educator or ritual coordinator, ensuring the seamless functioning of religious life. The chazan’s ability to evoke collective emotion makes him a bridge between text and heart, tradition and experience.

In essence, the chazan transforms prayer into a communal symphony of faith. His melodies elevate words into devotion, turning the synagogue into a space where sound itself becomes sacred. Through his voice, generations of Jews have found both continuity and consolation, linking their prayers to the timeless rhythm of Jewish worship.

CHUPPAH

The chuppah (חופה, wedding canopy) is one of the most recognizable symbols in Jewish life, representing the home that a couple begins together at their marriage. The chuppah is a canopy—often made of fabric and supported by four poles—beneath which the bride and groom stand during the nisuin (נישואין, wedding ceremony). It symbolizes the new household they are establishing and the divine presence, or Shekhinah (שכינה, indwelling of God), that sanctifies their union. The open structure of the chuppah expresses hospitality, suggesting that the couple’s future home will be one of generosity, warmth, and inclusion.

The origins of the chuppah can be traced to biblical and rabbinic descriptions of marriage. In the Talmud (תלמוד, rabbinic code), the term chuppah refers to the space in which the couple consummates the marriage, but over time it came to designate the ceremonial canopy used at the wedding itself. Medieval Jewish communities formalized its public role, integrating it into the sequence of the wedding rites. The practice of holding the chuppah outdoors—often under the stars—developed from the desire to recall the divine promise to Avraham Avinu (אברהם אבינו, Abraham our forefather), whose descendants were said to be as numerous as the stars of heaven.

During the ceremony, the groom and bride stand beneath the chuppah accompanied by witnesses, family, and guests. The officiating rabbi (רב, teacher or spiritual leader) recites the Sheva Berachot (שבע ברכות, seven blessings), praising creation, joy, and love, and invoking divine favor upon the couple. The bride and groom then drink from a cup of yayin (יין, wine), symbolizing sanctification and shared destiny. The ceremony concludes with the breaking of a glass, commemorating the destruction of the Beit HaMikdash (בית המקדש, Temple) and reminding those present that even in moments of joy, the memory of loss must temper celebration.

The chuppah varies in design according to tradition and culture. In Ashkenazic communities, it is typically a simple cloth—sometimes a tallit (טלית, prayer shawl)—while Sephardic and Mizrachi customs may feature elaborate fabrics or family heirlooms. In modern Israel, outdoor ceremonies often use minimalist chuppot overlooking nature, merging ancient symbolism with contemporary aesthetics. Despite these variations, the chuppah’s form remains consistent in meaning: it is open on all sides, like the tent of Abraham and Sarah, representing a home that welcomes others and extends kindness outward.

Beyond its visual and ritual beauty, the chuppah encapsulates profound theological ideas. It embodies the sanctity of marriage as a partnership infused with holiness, responsibility, and joy. Standing beneath it, the couple reenacts the covenantal ideal that binds love to faith, intimacy to community, and human commitment to divine purpose. In this way, the chuppah transforms a moment of personal celebration into a universal affirmation of unity, creation, and enduring faith.

DREIDEL

The dreidel (סביבון, spinning top) is a four-sided toy traditionally played with during the Jewish festival of Chanukah (חנוכה, Dedication). Each side of the dreidel bears a Hebrew letter—nun (נ), gimel (ג), hei (ה), and shin (ש)—which together form the acronym for Nes Gadol Haya Sham (נס גדול היה שם, A great miracle happened there). In Israel, the final letter differs slightly: pei (פ) replaces shin, rendering the phrase Nes Gadol Haya Po (נס גדול היה פה, A great miracle happened here). The dreidel serves as both a children’s game and a cultural symbol commemorating the miracle of the oil that defines the Chanukah story.

The dreidel’s origins trace back to medieval Europe, where similar spinning tops were used for gambling and seasonal entertainment. Jewish communities adapted the custom during times of religious oppression, transforming it into a tool for preserving faith and education. According to later legend, when Greek authorities under Antiochus IV (אנטיוכוס הרביעי, Antiochus IV) forbade the study of Torah (תורה, Law), Jewish children would appear to play with dreidels while secretly studying sacred texts. Though apocryphal, this story captures the enduring Jewish theme of resilience through disguise and creativity under persecution.

The game itself is simple yet meaningful. Players take turns spinning the dreidel, wagering tokens such as coins, nuts, or candies. The letter that lands face up determines the outcome: nun means “nothing,” gimel means “take all,” hei means “half,” and shin (or pei) means “put in.” This playful structure reflects the cyclical nature of fortune and the balance between gain and loss—an echo of the larger historical experience of the Jewish people. The game’s joyful character also reinforces simcha (שמחה, joy), a key value in Jewish life, especially during a festival celebrating spiritual triumph over oppression.

Beyond recreation, the dreidel carries rich symbolic interpretation. In Kabbalah (קבלה, Jewish mysticism), its four letters correspond to aspects of the universe—the north, south, east, and west—or to the four kingdoms that have ruled over Israel throughout history: Babylon, Persia, Greece, and Rome. The spinning motion symbolizes the constant flux of existence and the hidden workings of divine providence. The small top that spins unpredictably yet always returns to balance mirrors the Jewish survival story: endurance amid upheaval, faith amid uncertainty.

GADNA

The Gadna (גדנ״ע, youth military training corps) is an educational and preparatory program in Israel designed to familiarize high school students with the principles of defense, discipline, and national service. The name is an acronym for Gdudei No’ar (גדודי נוער, youth battalions), reflecting its mission to cultivate civic responsibility and readiness among young citizens. Established before the founding of the Medinat Yisrael (מדינת ישראל, State of Israel), Gadna has played an important role in shaping the ethos of commitment and unity that underpins Israeli society.

The origins of Gadna date back to the 1940s, during the final years of the British Mandate (מנדט, Mandate) in Palestine. Amid increasing tensions and security challenges, Jewish leaders in the Yishuv (יישוב, pre-state Jewish community) recognized the need to train youth for eventual national defense. The organization formally took shape under the auspices of the Haganah (הגנה, defense organization), the underground militia that later became the core of the Tzva HaHagana LeYisrael (צבא ההגנה לישראל, Israel Defense Forces). After Israel’s independence in 1948, Gadna was integrated into the structure of the IDF as an official youth corps, bridging the gap between civilian education and military service.

Gadna programs are typically conducted during high school years and last several days to a week. Participants engage in basic training exercises such as physical fitness, field navigation, discipline, and teamwork. They also receive instruction in the history and values of the Tzahal (צה״ל, IDF), learning about the moral code known as Ruach Tzahal (רוח צה״ל, Spirit of the IDF), which emphasizes respect for human dignity, responsibility, and love of the homeland. The program’s central aim is not militarization but education—fostering self-confidence, cooperation, and understanding of national defense as a shared civic duty.

In addition to its practical aspects, Gadna holds deep cultural and social significance. It reflects the Israeli ideal of mamlachtiyut (ממלכתיות, state-mindedness), a principle championed by David Ben-Gurion (דוד בן גוריון, David Ben-Gurion) that stresses collective service and equality in national obligations. For many young Israelis, participation in Gadna is a formative experience that prepares them psychologically and emotionally for their forthcoming military service, while reinforcing the connection between personal growth and societal contribution.

Over the decades, Gadna has adapted to changing educational and security contexts. Programs today emphasize leadership, citizenship, and ethical decision-making, integrating environmental projects and community service alongside military orientation. International youth programs also participate, offering diaspora Jews a glimpse into Israeli culture and identity. The continued vitality of Gadna demonstrates Israel’s enduring commitment to combining education with civic responsibility, ensuring that the values of defense, solidarity, and service remain integral to the nation’s character.

GALUT

The galut (גלות, exile) is a foundational concept in Jewish history and theology, referring to the dispersion of the Jewish people from their ancestral homeland, Eretz Yisrael (ארץ ישראל, Land of Israel). More than a geographical condition, galut embodies a spiritual and existential state—the experience of alienation, longing, and perseverance outside the sacred land. From the Babylonian exile in the sixth century BCE to the modern diaspora, the theme of galut has shaped Jewish identity, culture, and religious consciousness across millennia.

The first major galut followed the destruction of the Beit HaMikdash (בית המקדש, Temple) in Jerusalem by the Babylonians in 586 BCE. This event marked a profound rupture in the covenantal relationship between the people and their land. Yet the response to exile became one of resilience and renewal. In Babylon, Jewish leaders such as Ezra (עזרא, Ezra) and Nehemiah (נחמיה, Nehemiah) laid the groundwork for rabbinic tradition, emphasizing study, prayer, and community as substitutes for Temple worship. Thus, even in displacement, Judaism evolved mechanisms to preserve continuity, demonstrating that holiness could be maintained anywhere through devotion and law.

A second major galut began after the Roman destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, leading to centuries of dispersion throughout the Mediterranean, Europe, North Africa, and later Asia and the Americas. This prolonged exile became a defining framework of Jewish existence, interpreted by the Talmud (תלמוד, rabbinic code) as both punishment and opportunity for spiritual refinement. Jewish thinkers viewed galut not only as historical consequence but as a divinely ordained mission: to bear witness to monotheism and ethical values among the nations while awaiting geulah (גאולה, redemption).

Culturally, galut produced a remarkable synthesis of adaptability and endurance. Communities developed diverse languages such as Yiddish (יידיש, Jewish-German language) and Ladino (לאדינו, Judeo-Spanish), reflecting both integration and distinctiveness. Rabbinic institutions like the beit midrash (בית מדרש, house of study) and the beit knesset (בית כנסת, synagogue) served as centers of learning and cohesion, enabling Jewish civilization to flourish even under exile’s constraints. The longing for Zion remained central to daily life, expressed in prayers such as “Leshanah haba’ah b’Yerushalayim” (לשנה הבאה בירושלים, Next year in Jerusalem), recited at Pesach (פסח, Passover) and Yom Kippur (יום כיפור, Day of Atonement).

In modern times, the experience and meaning of galut have evolved. The rise of Zionism (ציונות, Jewish national movement) in the nineteenth century reframed exile as a condition to be actively ended through return and statehood. The establishment of the Medinat Yisrael (מדינת ישראל, State of Israel) in 1948 was viewed by many as the beginning of redemption, though others saw galut as continuing spiritually until the full restoration of messianic peace. Today, millions of Jews live outside Israel, balancing attachment to their host countries with an enduring sense of connection to the ancestral land.

Ultimately, galut remains both a memory and a metaphor: a reminder of suffering and perseverance, distance and faith. Through it, Judaism transformed displacement into purpose, turning exile into a continuous quest for identity, justice, and return.

GEMARA

The Gemara (גמרא, rabbinic commentary) is one of the two central components of the Talmud (תלמוד, rabbinic code), alongside the Mishnah (משנה, oral law). Together they form the cornerstone of rabbinic Judaism, shaping Jewish law, philosophy, ethics, and interpretation for nearly two millennia. The Gemara records the analytical discussions, debates, and interpretations of generations of rabbis—known as Amoraim (אמוראים, interpreters)—who examined every phrase and nuance of the Mishnah to extract its full legal and spiritual meaning. Through its intricate reasoning, the Gemara transforms law into a living intellectual and moral discipline.

Two versions of the Gemara developed over time. The Talmud Bavli (תלמוד בבלי, Babylonian Talmud) was compiled in the academies of Bavel (בבל, Babylonia) between the third and fifth centuries CE, while the Talmud Yerushalmi (תלמוד ירושלמי, Jerusalem Talmud) was produced earlier in Eretz Yisrael (ארץ ישראל, Land of Israel). Although both are authoritative, the Babylonian Talmud became the dominant text in Jewish study due to its greater completeness and analytical depth. The Gemara within each version reflects its distinct historical context—the intellectual rigor of Babylonian academies versus the more concise style of the Palestinian schools.

The structure of the Gemara is dialogical. It preserves the oral nature of rabbinic teaching, using question-and-answer exchanges, hypothetical cases, and arguments known as sugyot (סוגיות, discussions). Terms such as kushya (קושיה, difficulty) and terutz (תירוץ, resolution) mark the flow of dialectical reasoning. Each passage often includes layers of commentary that intertwine law, narrative, ethics, and theology. The dynamic method of inquiry—known as pilpul (פלפול, sharp analysis)—encourages intellectual engagement and creative problem-solving, making study of the Gemara not a passive exercise but an act of participation in an ongoing conversation across centuries.

Central to the Gemara is the idea that divine will can be approached through reasoned interpretation. Its pages record both agreement and dissent, reflecting the pluralism inherent in Jewish law. Rather than imposing uniformity, the Gemara preserves multiple viewpoints, teaching that truth emerges through dialogue and complexity. As the rabbis famously state, “Elu v’elu divrei Elohim chayim” (אלו ואלו דברי אלוהים חיים, These and those are the words of the living God). This openness to multiplicity has shaped Jewish thought and jurisprudence, influencing not only religious life but also broader traditions of legal reasoning and ethics.

Throughout history, the Gemara has served as the foundation of study in the beit midrash (בית מדרש, house of study). Commentaries by scholars such as Rashi (רש"י, Rabbi Shlomo Yitzhaki) and the Tosafot (תוספות, supplementary glosses) further deepened its accessibility and complexity. In modern times, yeshivot and academic institutions worldwide continue to study the Gemara as a living text, blending devotion with intellectual rigor. Its enduring influence demonstrates Judaism’s unique synthesis of faith and reason, law and narrative, continuity and creativity.

GET

The get (גט, divorce document) is the formal legal instrument that terminates a Jewish marriage according to halacha (הלכה, Jewish law). Unlike civil divorce, which is processed through courts of the state, a get must be written and delivered according to strict religious procedures, ensuring that both parties—especially the woman—are released from marital obligations under Jewish law. The process reflects the legal precision and moral sensitivity of rabbinic tradition, balancing personal freedom with communal responsibility and divine command.

The requirement for a get originates in the Torah (תורה, Law), specifically in Sefer Devarim (ספר דברים, Book of Deuteronomy) 24:1, which states that if a man sends his wife away, he must write her a “sefer keritut” (ספר כריתות, document of severance). Rabbinic authorities elaborated this command into a detailed system of laws to prevent coercion, fraud, or ambiguity. The get must be handwritten by a qualified sofer (סופר, scribe) using ink on parchment, in the presence of two eidim (עדים, witnesses). It is then formally delivered by the husband to the wife, who accepts it voluntarily, thereby dissolving the marriage.

Every aspect of the get procedure is governed by precision. The text must include the full Hebrew names of both spouses, the date, and the exact location of the divorce, written without error or correction. The ceremony takes place under the supervision of a beit din (בית דין, rabbinical court), which ensures that the process complies fully with halacha. Once the document is handed to the wife and she receives it, the dissolution becomes effective, granting her the status of a free woman, or gerusha (גרושה, divorced woman), who may remarry according to Jewish law.

The ethical dimensions of the get process have long been a subject of rabbinic and communal concern. Jewish law prohibits the use of physical or emotional coercion, since a get must be given b’ratson (ברצון, of free will). However, in certain cases where the husband refuses to grant a get, religious courts may impose social or communal sanctions to encourage compliance. The plight of a woman unable to obtain a get—known as an agunah (עגונה, chained woman)—has spurred ongoing efforts within rabbinic and legal frameworks to prevent abuse and safeguard women’s rights while preserving halachic integrity.

In contemporary Jewish life, the get retains both legal and symbolic significance. It underscores the sanctity of marriage by requiring an equally sacred process for its dissolution. Even among secular couples, obtaining a get is often seen as essential to achieving closure and maintaining religious legitimacy for future generations. The enduring institution of the get reflects Judaism’s commitment to justice, dignity, and moral responsibility in personal relationships—values that have guided Jewish family law from biblical times to the present day.

HAMANTASHEN

The hamantashen (אוזני המן, Haman’s ears) are triangular pastries traditionally eaten during the Jewish festival of Purim (פורים, Lots). Filled with poppy seeds, fruit preserves, or chocolate, these pastries symbolize the downfall of Haman (המן, Haman), the villain in the Megillat Esther (מגילת אסתר, Book of Esther). The name derives from the Yiddish hamantaschen (“Haman’s pockets”), though in Hebrew they are called oznei Haman, recalling the punishment of the wicked minister whose plot to destroy the Jews of Persia was foiled through courage and divine providence.

The custom of eating hamantashen originated in Central and Eastern Europe during the Middle Ages and became one of the defining culinary symbols of Purim. Their three-cornered shape has inspired multiple interpretations. Some view it as representing Haman’s three-cornered hat, while others see it as a reference to the strength of the Jewish people resting on three patriarchs—Avraham, Yitzchak, and Yaakov (אברהם, יצחק, יעקב, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob). Another symbolic explanation connects the hidden filling to the theme of divine concealment in the Purim story, where God’s name never appears yet His presence guides the outcome.

Hamantashen are prepared with sweet dough, folded around fillings such as poppy seed (mohn), apricot, plum, or date paste. The poppy seed variety may carry biblical allusions, as poppy seeds symbolize abundance and fertility. In Ashkenazic (אשכנזי, Central and Eastern European) tradition, families bake them together in anticipation of the holiday, while Sephardic (ספרדי, Iberian and Middle Eastern) communities developed similar sweets such as folares or debla for Purim celebrations. Over time, hamantashen evolved into a beloved treat beyond the religious context, appearing in bakeries throughout the Jewish world year-round.

The act of eating hamantashen is both joyful and symbolic. During Purim, Jews fulfill the mitzvah of se’udat Purim (סעודת פורים, festive meal) and express happiness through food, drink, and giving gifts known as mishloach manot (משלוח מנות, food portions to friends). The pastries’ sweetness represents the reversal of sorrow into joy, echoing the verse from Esther 9:22—“from mourning to celebration.” Children especially associate Purim with these treats, costumes, and revelry, reinforcing the holiday’s themes of survival, humor, and faith.

In modern Jewish culture, hamantashen have taken on creative and multicultural variations—filled with chocolate, cheese, or savory ingredients. Despite these innovations, their essence remains unchanged: they are edible symbols of Jewish endurance and the triumph of good over evil. Each bite recalls the victory of faith and courage embodied by Esther and Mordechai, reminding Jews of every generation that deliverance often hides within ordinary acts of joy and remembrance.

CHANUKKAH

The Chanukkah (חנוכה, Dedication) festival commemorates the rededication of the Beit HaMikdash (בית המקדש, Temple) in Jerusalem after its desecration by the Seleucid Greeks in the second century BCE. Lasting eight days, Hanukkah celebrates the victory of the Maccabim (מקבים, Maccabees), a Jewish rebel group led by Yehudah HaMaccabi (יהודה המקבי, Judah the Maccabee), over the forces of Antiochus IV Epiphanes (אנטיוכוס הרביעי אפיפנס, Antiochus IV Epiphanes). More than a military triumph, Hanukkah symbolizes spiritual resilience and the triumph of faith and identity over assimilation and oppression.

The festival’s central ritual is the lighting of the chanukiah (חנוכיה, Hanukkah candelabrum), a nine-branched lamp distinct from the seven-branched menorah (מנורה, Temple candelabrum). One additional light, the shamash (שמש, helper candle), is used to kindle the others. Each night, another candle is lit, culminating in eight on the final evening. This practice commemorates the nes ha-shemen (נס השמן, miracle of the oil), when a single cruse of pure oil found in the desecrated Temple burned for eight days instead of one. The light of the chanukiah is placed visibly in windows or doorways, fulfilling the mitzvah of pirsumei nisa (פרסומי ניסא, publicizing the miracle), expressing gratitude and faith openly.

Beyond the miracle of the oil, Hanukkah reflects the broader struggle for cultural and religious autonomy. The Maccabean revolt, recorded in Sefer Maccabim (ספר מקבים, Book of Maccabees), was both a battle against foreign domination and an internal conflict over Jewish identity. The victory led to the establishment of the Hasmonean (חשמונאי, Hasmonean) dynasty and the reassertion of Jewish worship in the Temple. The word “Hanukkah” itself signifies dedication or re-consecration, marking the moment the altar was purified and restored to divine service.

Hanukkah traditions evolved over centuries, combining historical memory with festive joy. Foods fried in oil—such as levivot (לביבות, potato pancakes) and sufganiyot (סופגניות, jelly doughnuts)—commemorate the miracle of the oil. Children play with the dreidel (סביבון, spinning top), marked with the letters nun, gimel, hei, and shin, forming the phrase Nes Gadol Haya Sham (נס גדול היה שם, A great miracle happened there). Families also give gelt (מעות חנוכה, Hanukkah coins), reinforcing charity and celebration.

In modern times, Hanukkah has acquired renewed significance as a celebration of Jewish identity and continuity, particularly in the galut (גלות, diaspora). In Israel, it embodies national revival and independence; in the diaspora, it serves as a joyful affirmation of resilience. Through light, song, and remembrance, Hanukkah reminds Jews that even the smallest flame of faith can dispel vast darkness. Its enduring message—hope, renewal, and dedication—continues to inspire communities around the world.

HAVDALAH

The havdalah (הבדלה, separation) is the brief but deeply symbolic ceremony marking the conclusion of Shabbat (שבת, Sabbath) and the transition into the new week. Its purpose is to distinguish between the sacred and the ordinary—between the sanctity of rest and the rhythm of daily labor. The term derives from the Hebrew root badal (בדל, to separate), expressing the spiritual principle that holiness depends on awareness and discernment. By performing havdalah, Jews reaffirm that time itself is sanctified through mindfulness and gratitude.

The ceremony is traditionally conducted shortly after nightfall on Saturday, once three stars are visible in the sky, signaling the end of Shabbat. It requires three ritual elements: a cup of yayin (יין, wine), a container of fragrant besamim (בשמים, spices), and a multi-wicked ner havdalah (נר הבדלה, havdalah candle). Each object carries symbolic meaning. The wine represents joy and blessing, the spices revive the soul as it parts from the extra neshama yeterah (נשמה יתירה, additional soul) believed to accompany a person on Shabbat, and the candle’s flame symbolizes enlightenment and renewed activity for the coming week.

The blessing sequence begins with Borei peri hagafen (בורא פרי הגפן, Creator of the fruit of the vine), followed by Borei minei besamim (בורא מיני בשמים, Creator of various spices), and Borei me’orei ha’esh (בורא מאורי האש, Creator of the lights of fire). Afterward, the leader recites HaMavdil bein kodesh lechol (המבדיל בין קודש לחול, Who separates between sacred and profane), concluding with a sip of wine and the extinguishing of the candle in the remaining liquid. The mingling of fire and wine at the end represents the merging of Shabbat’s sanctity with the challenges of weekday life, illustrating the seamless flow between sacred time and worldly responsibility.

Havdalah is both intimate and communal. Families often gather in a darkened room, their faces illuminated by the braided flame as they reflect on the peace of the departing Sabbath. Some wave their fingers toward the light, observing its glow upon their nails as a reminder of human creativity, blessed anew each week. In many communities, melodies accompany the blessings, including the refrain “Eliyahu HaNavi” (אליהו הנביא, Elijah the Prophet), expressing hope for redemption and the coming of the Mashiach (משיח, Messiah).

In Jewish thought, havdalah extends beyond ritual to moral awareness. Just as one distinguishes sacred from ordinary time, individuals are called to discern between good and evil, justice and wrongdoing. The ceremony thus becomes a meditation on purpose and renewal, marking not an end but a beginning—the reentry into daily life guided by the spiritual clarity gained through rest. In every flicker of the havdalah flame, Jews are reminded that holiness can continue to illuminate the week ahead.

HERZL

Theodor Herzl (תיאודור הרצל, Theodor Herzl) is regarded as the visionary founder of modern Zionism (ציונות, Jewish national movement) and one of the most influential figures in Jewish modern history. His leadership and writings transformed the age-old yearning for return to Eretz Yisrael (ארץ ישראל, Land of Israel) into a concrete political project that culminated in the establishment of the Medinat Yisrael (מדינת ישראל, State of Israel). Herzl’s life embodied the synthesis of European intellect, Jewish consciousness, and pragmatic activism that redefined Jewish identity at the turn of the twentieth century.